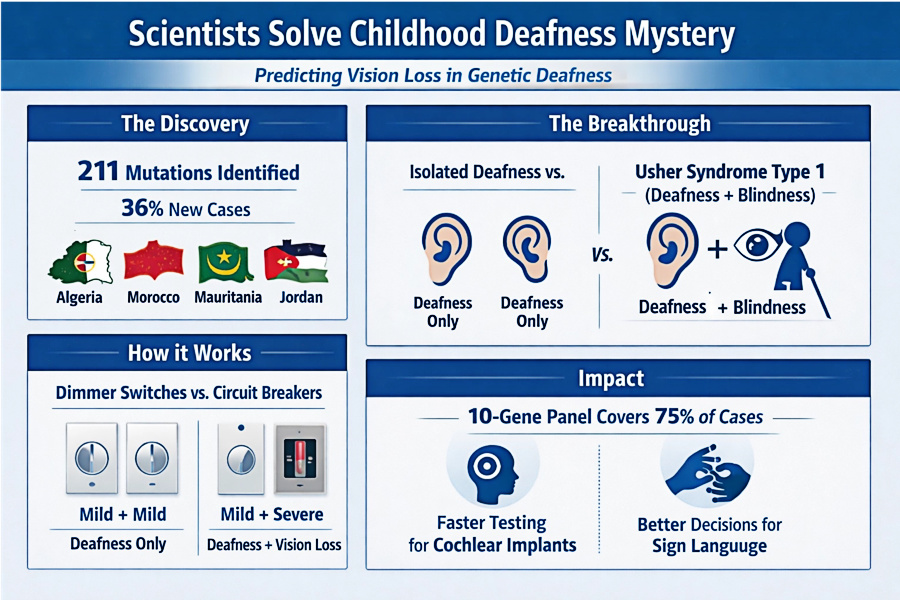

Researchers identified 211 distinct genetic mutations linked to childhood deafness in Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, and Jordan, with over a third being new. The breakthrough ends decades of diagnostic uncertainty for families wondering if their deaf child will lose their vision.

Why it matters

Parents and doctors can now predict if a child's deafness will remain isolated or progress into Usher syndrome type 1—a devastating condition adding balance disorders and blindness to profound hearing loss. Families previously waited years in uncertainty, making irreversible decisions about cochlear implants or sign language without knowing if vision loss would render those choices inadequate.

What changes

-

Families get clear answers about their child's future.

-

Doctors can recommend cochlear implants or sign language. If vision loss occurs, sign language is essential—cochlear implants rely on lip-reading and visual cues that won't remain available.

-

Kids with certain mutations should get regular eye exams to catch vision problems early.

By the numbers

-

Researchers analyzed 450 patients across Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, and Jordan.

-

The mutations were carried by 49 genes.

-

36% of mutations were previously unknown.

-

Just 10 genes account for 75% of cases in each country.

The breakthrough

Scientists solved a diagnostic puzzle that's forced genetic counselors to hedge for decades, unable to tell parents whether their child's deafness would remain isolated or progress to include blindness.

Certain genes cause isolated deafness or Usher syndrome depending on the inherited mutations.

How it works

The team discovered the pattern:

- Two copies of a "milder" mutation cause deafness only.

- One mild mutation plus one severe mutation causes deafness plus vision loss.

Think of dimmer switches versus circuit breakers. Two dimmer mutations reduce function but preserve vision. One dimmer plus one circuit breaker shuts down the visual system entirely.

"We hypothesized that these difficulties could stem from incomplete or inaccurate classification," says Christine Petit, head of the Hearing Therapy Innovation Laboratory at Institut Pasteur.

The context: Most severe congenital hearing loss is hereditary. Usher syndrome type 1 is exclusively inherited. Until now, genetic tests couldn't distinguish between the two paths.

A closer look

Responsible genes stay consistent across countries, but most mutations are family-specific. The exception? The GJB2 gene shows frequent, recurring mutations.

This changes genetic screening programs. Clinicians can start with a targeted 10-gene panel and get answers in days, instead of sequencing all 154 known deafness genes—a process that takes weeks and costs thousands.

Reality check

The mutation patterns identified apply specifically to North African and Middle Eastern populations. Families from other ethnic backgrounds may carry different mutations requiring separate analysis. The team sequenced known deafness-related genomic regions—undiscovered genes could still exist.

The bottom line

- This reclassification gives a precision tool to genetic counselors.

- Their next challenge is expanding the database to include mutations from other populations and building low-cost screening programs in regions with high consanguinity rates and hereditary deafness.

Healthy children's hearing starts here

A lot can happen in 15 minutes. Safeguard your child's development with a free, 15-minute hearing screening conducted by our expert audiologists. This quick check provides peace of mind, establishes a healthy baseline, and ensures your child is on track for learning and social success.

★ Call 708-599-9500 to schedule.

★ For facts about hearing loss and hearing aid options, grab your copy of The Hearing Loss Guide.

★ Sign up for our newsletter for the latest on Hearing aids, dementia triggered by hearing loss, pediatric speech and hearing, speech-language therapies, Parkinson's Voice therapies, and occupational-hearing conservation. We publish our newsletter eight times a year.

Don't let untreated hearing loss spoil your child's intellectual and social development.